Description: HTTP GET on resource ‘http://localhost:36682/testPath’ failed: unauthorized (401)

Type: HTTP:UNAUTHORIZED

Cause: a ResponseValidatorTypedException instance

Error Message: { "message" : "Could not authorize the user." }

Introduction to Mule 4: Error Handlers

In Mule 4, error handling is no longer limited to a Java exception handling process that requires you to check the source code or force an error in order to understand what happened. Though Java Throwable errors and exceptions are still available, Mule 4 introduces a formal Error concept that’s easier to use. Now, each component declares the type of errors it can throw, so you can identify potential errors at design time.

Mule Errors

Execution failures are represented with Mule errors that have the following components:

-

A description of the problem.

-

A type that is used to characterize the problem.

-

A cause, the underlying Java

Throwablethat resulted in the failure. -

An optional error message, which is used to include a proper Mule Message regarding the problem.

For example, when an HTTP request fails with a 401 status code, a Mule error provides the following information:

Error Types

In the example above, the error type is HTTP:UNAUTHORIZED, not simply UNAUTHORIZED. Error types consist of both a namespace and an identifier, allowing you to distinguish the types according to their domain (for example, HTTP:NOT_FOUND and FILE:NOT_FOUND). While connectors define their own namespace, core runtime errors have an implicit one: MULE:EXPRESSION and EXPRESSION are interpreted as one.

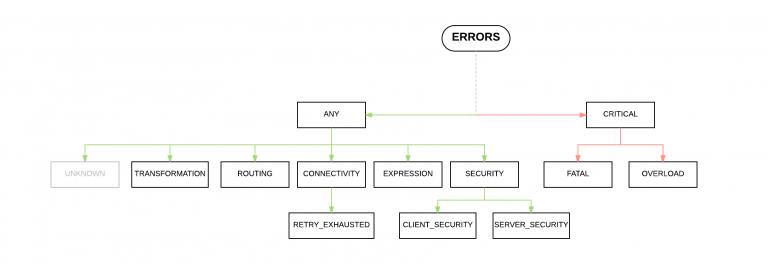

Another important characteristic of error types is that they might have a parent type. For example, HTTP:UNAUTHORIZED has MULE:CLIENT_SECURITY as the parent, which, in turn, has MULE:SECURITY as the parent. This establishes error types as specifications of more global ones: an HTTP unauthorized error is a kind of client security error, which is a type of a more broad security issue.

These hierarchies mean routing can be more general, since, for example, a handler for MULE:SECURITY catches HTTP unauthorized errors as well as OAuth errors. Below you can see what the core runtime hierarchy looks like:

All errors are either general or CRITICAL, the latter being so severe that they cannot be handled. At the top of the general hierarchy is ANY, which allows matching all types under it.

It’s important to note the UNKNOWN type, which is used when no clear reason for the failure is found. This error can only be handled through the ANY type to allow specifying the unclear errors in the future, without changing the existing app’s behavior.

When it comes to connectors, each connector defines its error type hierarchy considering the core runtime one, though CONNECTIVITY and RETRY_EXHAUSTED types are always present because they are common to all connectors.

Error Handlers

Mule 4 has redesigned error handling by introducing the error-handler component, which can contain any number of internal handlers and can route an error to the first one matching it. Such handlers are on-error-continue and on-error-propagate, which both support matching through an error type (or group of error types) or through an expression (for advanced use cases). These are quite similar to the Mule 3 choice (choice-exception-strategy), catch (catch-exception-strategy), and rollback (rollback-exception-strategy) exceptions strategies However, they are much simpler and more consistent.

If an error is raised in Mule 4, an error handler is executed and the error is routed to the first matching handler. At this point, the error is available for inspection, so the handlers can execute and act accordingly, relative to the component where they are used (a Flow or Try scope):

-

An

on-error-continueexecutes and uses the result of the execution as the result of its owner (as though the owner completed the execution successfully). Any transactions at this point are committed, as well. -

An

on-error-propagaterolls back any transactions, executes, and uses that result to re-throw the existing error, meaning its owner is considered to be “failing.”

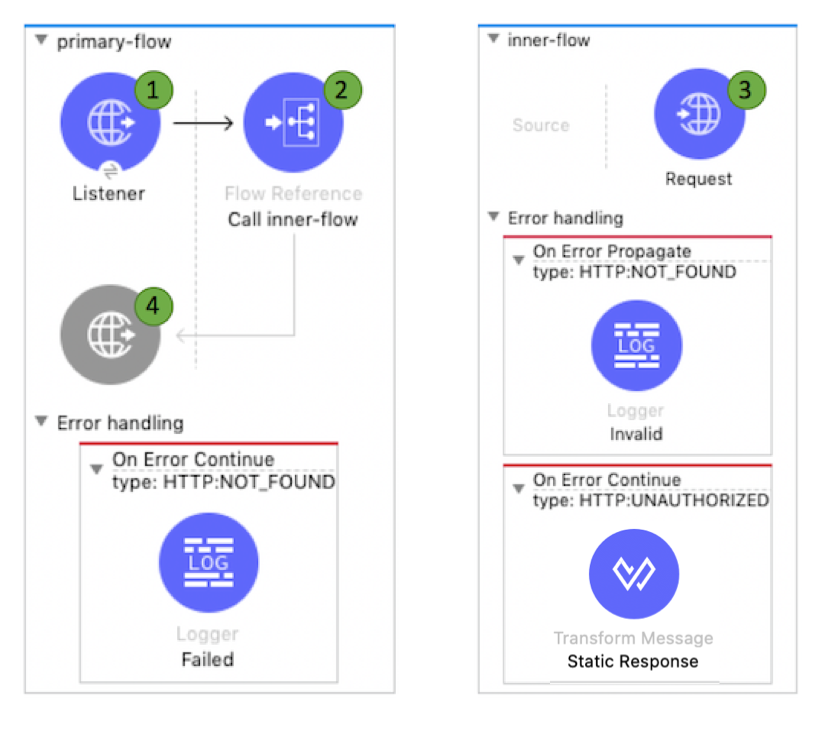

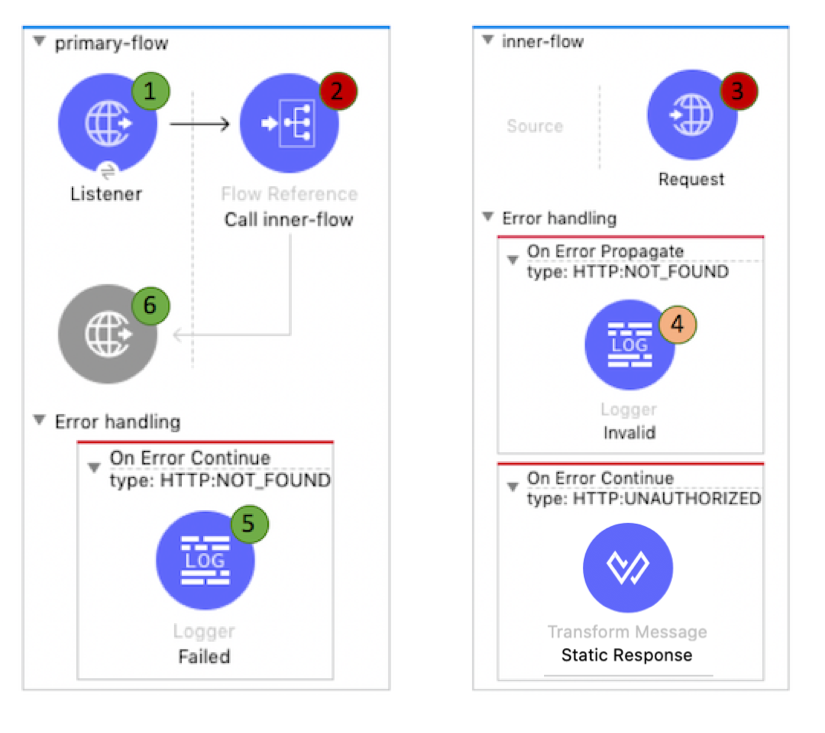

Consider the following application where an HTTP listener triggers a Flow Reference component to another flow that performs an HTTP request. If everything goes right when a message is received (1 below), the reference is triggered (2), and the request performed (3), which results in a successful response (HTTP status code 200) (4).

If the HTTP request fails with an HTTP:NOT_FOUND error (see 3 below) because of

the error handler configuration in inner-flow, the error is propagated (4), and the

Flow Reference component fails (2). However, because primary-flow handles the

error with on-error-continue, the Logger it contains (5) executes, and a

successful response (HTTP status code 200) is returned (6).

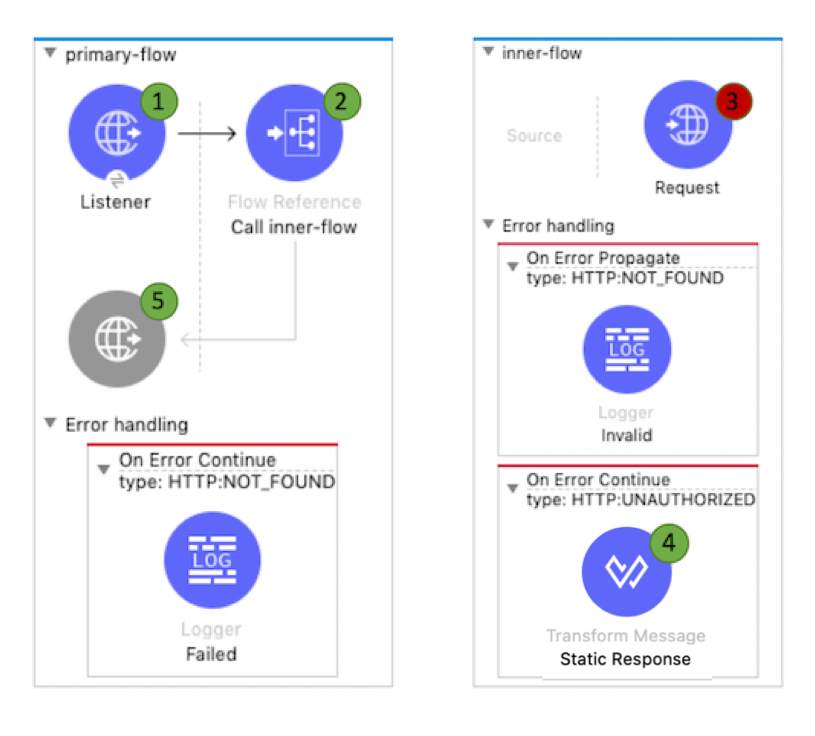

If the request fails with an unauthorized error instead (3), then inner-flow handles it with an on-error-continue by retrieving static content from a file (4). Then the Flow Reference component is successful as well (2), and a successful response (HTTP status code 200) is returned (5).

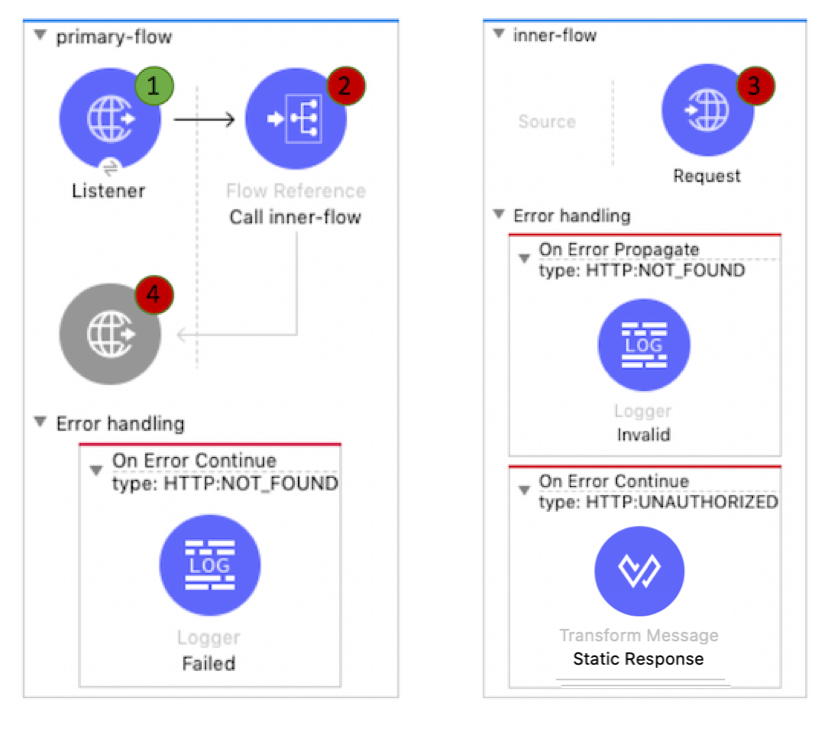

But what if another error occurred in the HTTP request? Although there are only handlers for NOT_FOUND and UNAUTHORIZED errors in the flow, errors are still propagated by default. This means that if no handler matches the error that is raised, then it is re-thrown. For example, if the request fails with a method not allowed error (3), then it is propagated, causing the Flow Reference component to fail (2), and that propagation results in a failure response (4).

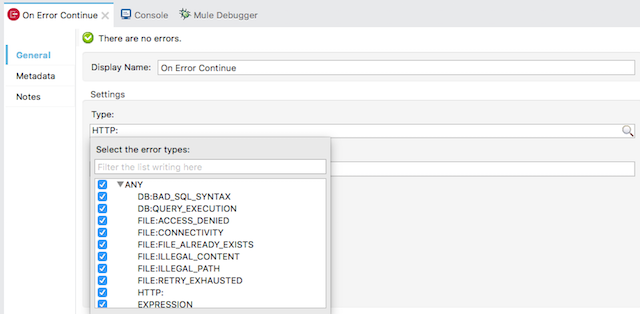

The scenario above can be avoided by making the last handler match ANY, instead of just HTTP:UNAUTHORIZED. Notice how, below, all the possible errors of an HTTP request are suggested:

Or should it be fields?

You can also match errors using an expression. For example, since the Mule Error is available during error handling, we can use it to match all errors with the HTTP namespace:

image::error-handling-expression.png["An On Error Continue general fields showing an expression to handle HTTP errors"]

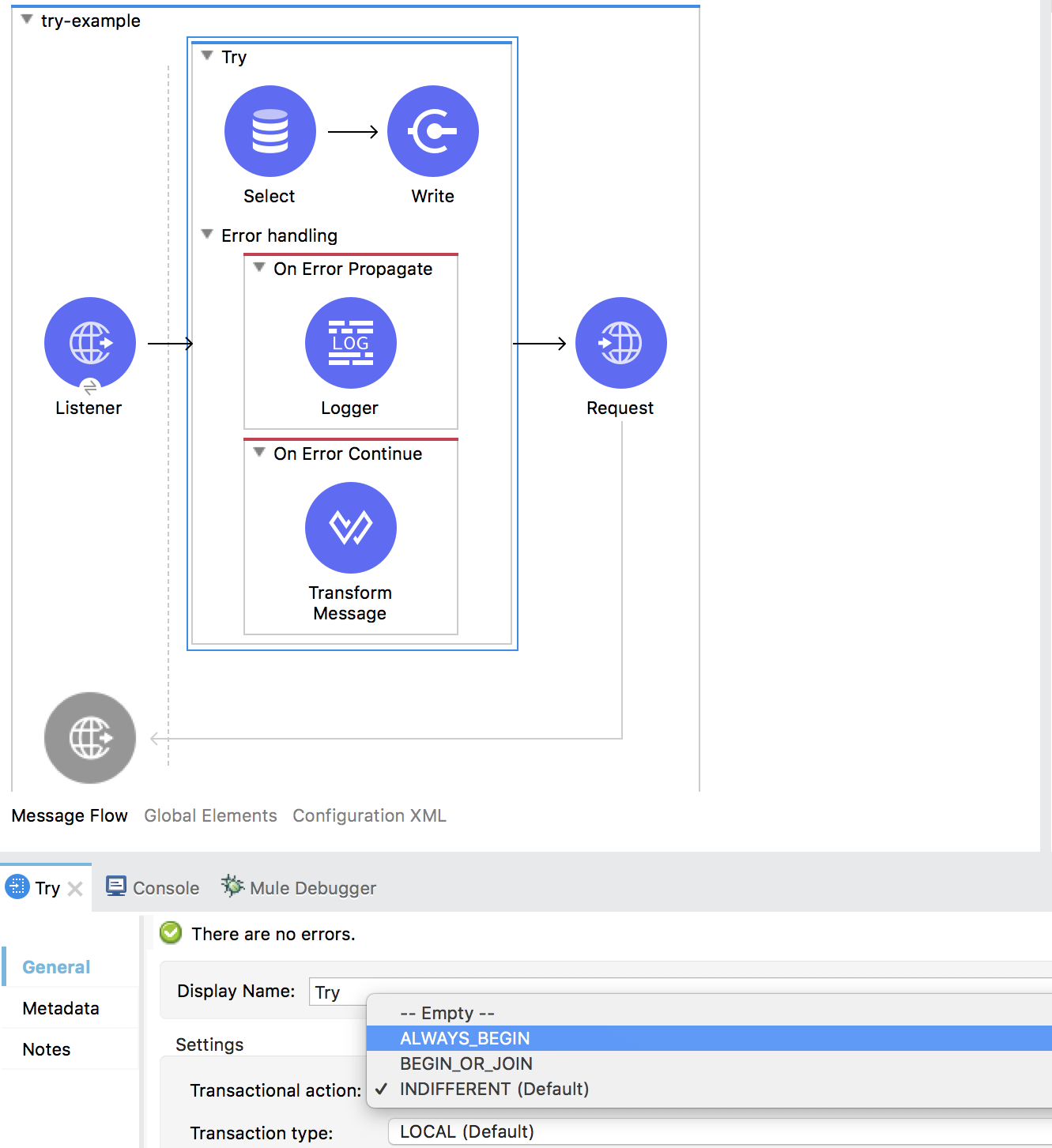

Try Scope

For the most part, Mule 3 only allows error handling at the flow level, forcing you to extract logic to a flow in order to address errors. In Mule 4, we’ve introduced a Try scope that you can use within a flow to do error handling of just inner components. The scope also supports transactions, which replaces the old Transactional scope.

In the previous example, On Error Propagate component is configured to propagate database connection errors, causing the try to fail and the flow’s error handler to execute.

On Error Continue component is configured to handle any other error. The Try scope’s execution is successful for that case, which means that the flow’s execution continues with the next processor, an HTTP Request operation.

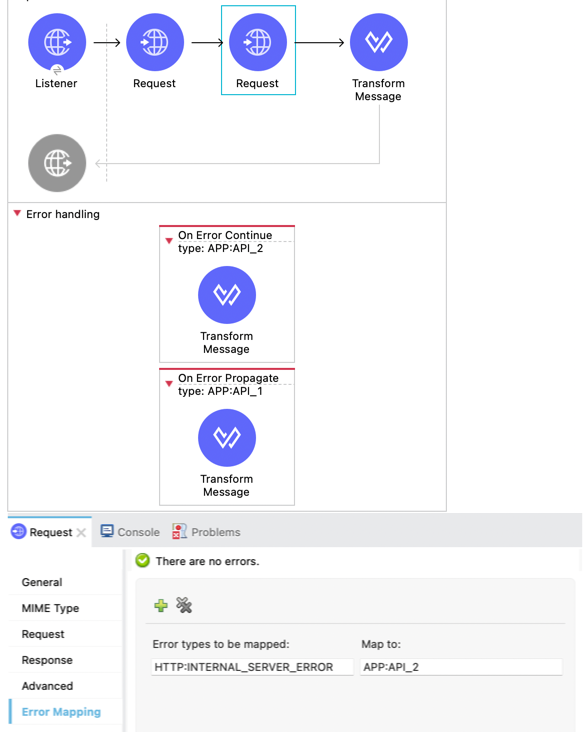

Error Mapping

Mule 4 now also allows for mapping default errors to custom ones. The Try scope is useful, but if you have several equal components and want to distinguish the errors of each one, using a Try on them can clutter your app. Instead, you can add error mappings to each component, meaning that all or certain kind of errors streaming from the component are mapped to another error of your choosing. If, for example, you are aggregating results from 2 APIs using an HTTP request component for each, you might want to distinguish between the errors of API 1 and API 2, since by default, their errors are the same.

Mapping enables you to customize error handling by routing errors to the appropriate error handler. The following example routes errors from the first Request operation to the error handler APP:API_1 and routes errors from the second Request operation to APP:API_2. To apply different handling policies if the APIs go down, the example maps HTTP:INTERNAL_SERVER_ERROR to each error handler. One mapping propagates the error if it comes from the first API. The other handles the error if it comes from the second API.